Check out https://apastyle.apa.org/ for APA questions!

Page 2 of 7

Writing an effective abstract is an exercise in concise thought articulation. It is sometimes difficult to streamline complex theories or condense research methods. This worksheet from San José State University provides the language to use when crafting an abstract, and they have a variety of templates based on genre for you to adapt. It is also useful to understand these terms as novice researchers because they will help you speed-read through hits on databases. Check it out!

Citation Machine in Google Docs

Did you know that there is an ad-free citation machine build into Google Doc? You can access for free, and it will even generate your in-text citations (just not the page numbers). Check it out! Just be sure to double check your work!

Objective vs. Subjective Pronouns: Rules and Common Mistakes

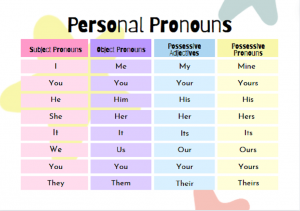

Pronouns are essential in our language, allowing us to avoid unnecessary repetition and make our writing and speech more fluid. However, understanding the difference between objective and subjective pronouns can be tricky for many writers. Let’s break down the rules for both and highlight some common errors to help clarify when and how to use them correctly.

You are likely familiar with the chart below that lists the personal pronouns by case.

Key Rules for Using Subjective and Objective Pronouns

-

Subjective Pronouns as the Subject of the Sentence Subjective pronouns always come before the verb in a sentence, as they are the ones performing the action.

- Correct: I went to the store.

- Incorrect: Me went to the store. (Here, “me” is incorrectly used as the subject.)

-

Objective Pronouns as the Object of the Sentence Objective pronouns always come after the verb or a preposition. They receive the action of the verb.

- Correct: She called me.

- Incorrect: She called I. (“I” is a subjective pronoun, so it doesn’t work here as the object.)

-

Pronouns After Prepositions When a pronoun follows a preposition, it should always be in the objective case.

- Correct: He is sitting next to her.

- Incorrect: He is sitting next to she.

Frequent Errors with Subjective and Objective Pronouns

Now that we know the basic rules, let’s explore some common mistakes people make when using subjective and objective pronouns.

1. Using the Subjective Pronoun After “Than” or “As”

One of the most frequent errors is confusing subjective and objective pronouns in comparisons with “than” or “as.” For example:

- Incorrect: She is taller than I.

- Correct: She is taller than me.

In this case, “me” is the object of the implied comparison (e.g., “She is taller than I am”), so it should be in the objective case.

2. Using “I” When It Should Be “Me”

This is a particularly common error in compound sentences, especially when pronouns are combined with other people’s names or pronouns. For instance:

- Incorrect: My sister and I went to the park.

- Correct: My sister and me went to the park. (The verb “went” is not done by both “my sister and I” as a compound subject, but rather “my sister and me” as the object of the preposition “to.”)

3. Confusing “Who” and “Whom”

The words “who” and “whom” are often confused because they both relate to people, but they serve different roles. “Who” is subjective (used as the subject of a sentence), while “whom” is objective (used as the object).

- Incorrect: Who did you see at the party?

- Correct: Whom did you see at the party?

However, in modern, casual English, “who” is often used in place of “whom” (especially in speech). Still, it’s best to use “whom” in formal writing when it’s acting as the object.

4. Misusing “They” as Singular

While “they” has become widely accepted as a gender-neutral, singular pronoun, in traditional grammar, it was strictly plural. Still, using “they” as a singular pronoun, though a relatively recent shift, is grammatically correct when referring to a person whose gender is unspecified or when respecting their gender identity.

- Correct: If anyone calls, tell them I’m not here.

- Incorrect: If anyone calls, tell him or her I’m not here.

Conclusion

The rules surrounding subjective and objective pronouns are straightforward once you know their roles in a sentence. Remember: subjective pronouns (I, you, he, she, we, they) perform the action of the verb, while objective pronouns (me, you, him, her, us, them) receive the action or follow a preposition. Avoid common mistakes by paying close attention to how pronouns function within sentences and ensuring that they agree with the sentence’s structure. Keep these rules in mind, and your pronoun usage will improve dramatically!

——————————————————————————————————————–

Other Pronoun Rules:

However, some of those, particularly she/her and he/his, are traditionally associated as being either masculine or feminine. For that reason, gender neutral pronouns have been widely adapted. Here are some examples:

Gender Neutral Pronouns

| SHE | HER | HER | HERS | HERSELF |

| HE | HIM | HIS | HIS | HIMSELF |

| zie | zim | zir | zis | zieself |

| sie | sie | hir | hirs | hirself |

| ey | em | eir | eirs | eirself |

| ve | ver | vis | vers | verself |

| tey | ter | tem | ters | terself |

| e | em | eir | eirs | emself |

Find a brief overview of the grammatical rules associated with gender inclusive pronouns with a more extensive list with context please explore the resource here.

The best way to integrate inclusive pronouns into your speech and writing is to practice the rules of usage. This a platform that will allow you to review the rules quickly before allowing you to test your knowledge here.

Lots of students struggle with indenting the second lines of their references on their works cited page. Sometimes they use spaces or tabs, which create a sloppy and inconsistent reference page. There are many easy ways to insert the hanging indent, which will visually enhance your reference list. It will also save you time.

1.) There are two easy ways to do it in MS Word, and this video demonstrates both methods: How to Create Hanging Indents in MS Word

2.) There are two similar ways to do it in Google Docs and this video demonstrates both methods: How to Create Hanging Indents in Google Docs

By Kristen LeFebvre

As an occupational therapy student, you will have various writing assignments. Below are some general tips for writing in occupational therapy classes.

- Try to use the language of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF-4) whenever possible in assignments.

- The first time you are using an acronym, you need to write out the whole thing and put the acronym in parentheses. For example: American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Once you use the acronym, you can use it throughout your paper without writing it out.

- In formal writing, including research, remove pronouns such as “I”, “me”, and “you”. If you are writing a reflection, you may use “I”, “me”, and “you”.

- Use the word “client” when referring to the person you are working with instead of the word “patient”. The word “client” emphasizes collaboration with the person and takes a step away from the medical model.

- When researching, try to find articles within the past 5 years (if possible). This gives you the most current evidence.

- When writing a pediatrics case study, make sure you address parental concerns and goals.

- Most papers will be written in APA format. You can find information on APA format here: https://sites.scranton.edu/writingcenter/archives/tag/apa

- Do not be afraid to reach out to your professor for clarifications on the assignment. If you are confused, always ask

Some terminology you may come across:

- Paradigm: A paradigm is made up of core constructs, focal viewpoints, and values. A paradigm provides an identity for a profession.

- Occupational therapy started with the paradigm of occupation then transitioned to the mechanistic paradigm. After that, it transitioned again to the current paradigm which is the contemporary paradigm.

- Theory: A way of thinking about a phenomenon, comprised of concepts and principles

- Conceptual Practice Model: helps to link theory to into real-world practice.

- Ex. Model of Human Occupation (MOHO), Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E), Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP)

By: Stephanie Lehner

To all of you who may be new to writing or have been doing it for a long time, I am writing this blog to express my opinion on the importance of practicing and trying to better your writing skills rather than utilizing AI to write for you. Since we are now in an era where AI is becoming more familiar with human tendencies and is gaining an ever-increasing ability to do what people once did alone, it is important not to lose vital communication skills.

When I entered college as a freshman, I was scared to go to the Writing Center because it was unfamiliar to me. I also felt uncomfortable going to in-person appointments, as I did not yet know many people at the university and I was afraid of having my paper ripped to shreds. Instead, I would write my papers and spend hours poring over each line to edit them properly. After I received my grade, I would sometimes be disappointed with the grammar errors that I missed. As such, when I became a Writing Consultant during my sophomore year, I started making appointments to utilize the Writing Center’s services myself. As I began to better my writing by receiving constructive feedback and helping others with their papers, I regretted not going sooner, for I could have saved myself a lot of time and grief freshman year, while also learning from my mistakes more quickly from more experienced writers. The fear that I initially had was quelled, since I saw how patient the other Writing Consultants were with me. They truly wanted to help me to further improve, and that is the mentality that I also share when I work with students.

Now as a senior, I can confidently say that my writing has become drastically better since my freshman year. However, it has taken a significant amount of time to get where I am. I also share the mindset that it is much more beneficial for an individual to start with writing that you, yourself, may deem ‘bad’ because you can always improve. Oftentimes, what you may deem to be ‘bad’ is in reality not bad at all and changing a practice or receiving a few tips could go a long way. This sentiment is similar to the quote that I chose, which hangs in the Writing Center: “Start writing no matter what. The water does not flow until the faucet is turned on.” This could apply to papers where you feel like you’re experiencing writer’s block but could also help you to get started in your writing journey. All it takes is for you to put pen to paper, or sometimes, your fingers to your computer, and let the ideas flow.

AI definitely is a great tool and may be able to produce papers that could pass as your own. However, you will not feel the same excitement when you get your grade back. You will also not feel the satisfaction of reading your finished paper thinking, “Wow! I came up with that!” In my experience, feelings such as these form after hours of brainstorming, writing, and proofreading, and this level of hard work makes the writing process much more rewarding. You never know what doors could be opened for you once you become a strong writer. Writing is an essential skill in many professions from scientists who publish research papers to copywriters for skincare companies to script writers of movies. Perhaps that skill will impress a future employer or maybe you will be asked to be a keynote speaker for a graduation or conference. Regardless, I think it is extremely important to have confidence in your abilities no matter where you are in the writing process. AI will never replace humans, especially when it comes to evoking feeling and your personal thoughts and experiences in your writing. As such, I

have a challenge for you: don’t be intimidated about coming to the Writing Center. Don’t think to yourself that your writing is ‘bad.’ Don’t rely on AI to write something for you when you could write a masterpiece that is 10 times more eloquent. Instead, have confidence in yourself and your abilities. Utilize the Writing Center’s resources to improve and come frequently if you need help. Lastly, never stop believing that one day, you could have wonderful writing that may help others do what you were once afraid of. So, put your pen to paper, and let the ideas flow!

By Myracle Brunette

Imagine this: You finally finished writing a paper for a class. Once you go to revise it, you come across a sentence that feels like it just goes on and on without any breaks or pauses. You might catch yourself struggling to understand what’s trying to be said. You might even catch yourself saying, “wow that’s a really long sentence.” If so, you’ve most likely encountered a run-on sentence. Run-on sentences are common to run into when it comes to writing. If you happen to have any in your paper, don’t worry. We’ve all been there, and they can easily be fixed.

What Really Is A Run-On Sentence?

Now you might be wondering, “what really is a run-on sentence?” A run-on sentence is when two independent clauses are joined together improperly. They are sentences without proper punctuation or appropriate conjunctions to separate them. This can involve using too many conjunctions and omitting punctuation such as commas, periods, and semicolons. This can lead them to oftentimes lack clarity and confuse the reader. There are 2 different types of run-on sentences. They are fused sentences and comma splices.

Fused Sentences:

A fused sentence is when two or more complete sentences are joined together without punctuation. They are fused together as if they were only one thought, and this can change what the writer was actually trying to tell the reader. For example, “I like dogs dogs can smell sometimes.” This sentence contradicts itself and can confuse your reader. Instead, the sentence can read, “I like dogs, but they can smell sometimes.” Notice how I just added a coordinating conjunction to join the two ideas and transform the sentence. You can also break up the sentence completely with a period to make it two separate ones, but since the writer is saying that they like dogs and then states something that they dislike about them, it would be best to use “but” to show that idea better.

Comma Splices:

A comma splice is when two or more complete sentences are incorrectly joined by just a comma. It normally looks like this: “main clause, main clause.” For example, “I love to read books, I also enjoy watching movies.” We can fix a comma splice the same way we can fix a fused sentence. We can either make the two clauses into two complete sentences, use a coordinating conjunction, use a semicolon, or use a subordinating conjunction. The ideal way to correct the sentence I provided would be to simply break it into two complete sentences.

How Can I Fix My Run-On Sentence?

In case you missed the examples I provided of run-on sentence solutions, I’ve listed them below:

- Check for Comma Splices

- Utilize Coordinating Conjunctions

- Use a Semicolon.

- Utilize Subordinating Conjunctions

How To Avoid Them:

Working on run-on sentences can be hard, especially when trying to avoid them. I’ve provided some resources below to help you exercise your brain a little. The more one works on improving their skills, the faster they improve them.

My personal favorite resource is Grammar Bytes. This website has some exercises that can help you work on your skills for more than just run-on sentences. It also provides more rules on comma splices and fused sentences. https://chompchomp.com/exercises.htm#Comma_Splices_and_Fused_Sentences

We also recommend Purdue Owl as a great resource for help with run-ons.

Verbix is a free website where you can enter a verb in most languages, and it will give you all of the verb forms in each tense with examples. It will also suggest translations of the verb in other languages, and it will provide closely related verbs within the target language with examples.It’s a helpful tool for all students looking to integrate more academic verbs, but it is particularly useful for English language learners.

by Dimitri Bartels-Bray

Beginning the graduate school application process might seem like a daunting task. Sure, you’ve applied to internships or scholarships in the past couple of years, but when’s the last time you sat down and applied to a school? Probably over four years ago. What’s worse is that this time, there’s the personal statement.

Fortunately, applying to graduate school, regardless of which type of degree you anticipate getting, does not need to be as harrowing as it initially seems. Today, we’ll be helping you step-by-step to create the personal statement, one of the largest pieces of your application. Let’s dive right in:

- List Your Goals

It might seem straightforward, but often students jump into the writing without doing the planning first! Schools normally restrict personal statements to only one or two pages, which isn’t a whole lot of room to tell them about yourself and your aspirations. That’s why it’s important to go in knowing the main points you plan to get across. Consider questions like:

- What inspires you to go into this field?

- What skills or activities best prepare you for this field?

- Why are you applying to this school in particular?

- Create an Outline

Once you have your goals listed out, consider creating an outline. This is a great way – as it

is with any paper – to expand and organize your ideas. To begin, consider this common format:

- Introduction: The introduction often begins with a story or some sort of theme that can tie the piece together. This is the more personal aspect of your statement, and often describes the moment you recognized your aspirations. It needs to pull the reader in and lead into your skills in some way.

- Body Paragraph(s): This/these paragraph(s) focus on describing your experiences and skills. What have you done in relation to the field you plan to enter? Even if you think there are no direct links between your work now and your work in the future, consider the skills obtained during internships, work, or other activities. For instance, perhaps you are a philosophy major aspiring to gain an MBA, and you had an internship that focused on creating presentations and strengthening communication skills. This is also a great location to end your template if you plan on applying to multiple schools. That way, you only need to make minor adjustments (if any) for each application before writing the concluding paragraph.

- Conclusion: Here, focus on mentioning the school itself. It’s important to connect yourself with the institution. Consider if there are research opportunities or institutes unique to the school, for instance. What draws you specifically to this school? The end of this paragraph is also the prime location to reconnect to the story, theme, or idea from your introduction; it doesn’t need to be lengthy, but a good conclusion sentence will be able to wrap it all up like a present with a ribbon on top.

- Write, write, write!

- Revise and Repeat

After you finish writing your rough draft, it’s best to walk away for a bit if you have the time, which is why we recommend beginning the writing process as early as possible. Not looking at your work will enhance the editing process as it won’t be as fresh in your mind – it’s much easier to critically edit when the document isn’t familiar!

Once you’ve let it sit for a while, return to the document, and read it aloud. Reading it aloud is the easiest way to check for clear grammar and flow errors. Also take this initial session to ensure that you cover all the points you hoped to discuss. Remember that this is the chance for admissions’ officers to get to know YOU. After reading, make any necessary edits, and rewrite portions if you find your statement lacking information.

After you feel that you have a solid draft with all the information you want to include, this is a great time to get feedback from others. Visit your school’s career or writing center to go over it with you; ask professors in your field if they’d have the chance to read it. Gain as much feedback as possible. After each time, return to your paper and adjust. Repeating this process again and again will help gather different perspectives on your work and ensure that your ideas translate to an outside audience.

Though we hope these steps help you in completing you, we understand how overwhelming it can be to begin the process. In addition to offering these guidelines and our services, here are some external resources that might help:

- More Instructions and Guidelines:

- Student Samples: