Our favorite resource for literature reviews was created by The University of Waterloo. First, these modules define what literature reviews are, where they appear, and why they are beneficial. The website talks about discipline-specific writing conventions and the different organizational approaches. Then, it walks writers through the process of composing literature reviews in a highly visual and interactive guide. The images, in particular, can help writers understand the various forms of knowledge gaps. Ultimately, this is a quick but highly beneficial resource that can guide novice writers who are unfamiliar with the conventions of literature reviews.

Category: General Writing Tips (Page 2 of 4)

- Philosophy papers are not reports, or research papers, or reflection papers. Generally, they ask students to use their reasoning skills to defend a particular idea or test the validity of an argument. Considering that, look at the prompt. Does your instructor want you to apply a philosophical argument to a new situation? Does the prompt ask you to amend an existing argument? Or object to an argument? Read the prompt closely and take a look at these frequently used tasks to better understand the prompt.

- Choose a stance to argue for or against. Do not choose both sides or neither side. Playing the middle-ground can be much more difficult and might require a longer paper.

- Have a precise thesis statement that defines your stance, how you will prove your stance, and why your stance should matter to your reader. Check out some adaptable thesis templates here.

- Define any abstract terms, concepts, or perspectives before you dive into your draft. Have the definitions accessible so you can use them correctly to support your reasoning. Make sure you are using philosophical terms correctly. Here’s a brief guide with frequent concepts. Here is a guide with vocabulary to help you describe arguments as you analyze them.

- Make a detailed outline before you start writing. When dealing with abstract concepts, it’s easy to go on tangents or lose focus. One possible way to approach these papers is to use the They Say/I Say method, which is further explained here. Another point-by-point method of organization is here.

- Use your instructor’s office hours once you have a detailed outline to make sure you are on track for success.

- Write a brief introduction. Be concise and respond directly to the main question within the prompt.

- Don’t use too many direct quotes. Remember, philosophy instructors generally want to see your reasoning skills, not your summary skills. Select and integrate material from others that best illustrates or supports your idea. Don’t let them overshadow your ideas.

- Communicate your stance and thought process clearly. Avoid all vague words (a lot, stuff, things) and empty language (basically, just, great, fine) unnecessary adverbs (really, very, importantly) that can distract your reader. Make sure you are choosing the most appropriate words.

-

-

- Use examples and illustrations to demonstrate your thoughts.

- Use transitions and signposts to indicate how ideas relate to each other.

- It’s wise to have a peer review your argument to make sure it’s clear with no gaps in your logic.

-

- Be confident—don’t preface your ideas behind phrases like “In my opinion,” “I believe,” or “For me at least,” because it discredits your argument.

Other Resources

| Student Sample Papers | An Annotated Student Sample Paper |

| Common Issues in Philosophy Papers | Examples of What Not To Do |

| Strong Writing vs. Poor Writing

in Philosophy Papers |

Examples of Student Writing |

By Danielle DePasquale

In an effort to craft properly paced sentences, it can be tricky deciding which punctuation marks to use. We use periods, question marks, and exclamation marks in our writing without hesitation, as we are aware of the grammatical implications and emphasis they contribute. But, when it comes to commas, colons, and semicolons, we are often unsure. So, what is the difference between using a comma, colon, and semicolon? Over the past few years, this has been a frequently asked question during writing center appointments. While these marks are close in proximity on the keyboard and similar in appearance, each have a different role when formulating sentences. Let’s start with commas. Commas serve many purposes, but they most commonly function as pauses within a sentence. When writing, I often read my sentences aloud and put commas where I naturally take breaks when reading. Ultimately, their use or omission is up to the discretion of the writer. However, as in most principles, I advise against over or under use. I also wanted to make a quick mention of the Oxford comma, as this is another FAQ. When listing items or ideas, some may choose to use the Oxford comma, which is the last comma in the list. However, it is a more of a style choice. My recommendation is that if you choose to use the Oxford comma, just ensure that it is placed in the correct part of the sentence. The next debate is the use of a colon versus a semicolon. To put it simply, colons are used to introduce as statement. I like to think of a colon as an equal sign, as it precedes the announcement of an idea or quotation. In contrast, a semicolon connects two separate sentences that are related. The trick with using a semicolon is to ensure that each idea on either side of the semicolon reads as a full sentence. For more information, I provided a link with some examples of correct and incorrect uses of each punctuation mark in the hopes of making the differences clearer. Using such punctuation accurately will only enhance one’s writing sophistication and clarity.

Test your knowledge with this comma quiz.

by Josh Vituszynski

I spent this past intercession on just about the last thing any right-minded student would want to do over break. I wrote an 80 page paper. You might ask, why did I imprison myself to the harsh confines of Microsoft Word during what should have been a month of freedom? Because I am working on a research project, and I spent the fall semester not only brainstorming, but also second guessing myself and my ideas. I continually hesitated to put words on the page because I was worried that I would not be able to handle writing a paper of such a large length. Going into the winter break, I knew I had to get a first draft together before the spring semester began. So, I decided to stop ruminating over my writing abilities and committed myself to writing what I needed to write. I decided that I needed to stop worrying so much about whether I was happy with the initial product. After all, who is totally happy with a first draft? If writing a paper is like shooting darts, and that final draft is the bullseye, then the first draft is target practice. Sure, it might be humbling to take those first few shots and nearly miss the target entirely, but most people cannot experience the gratification of hitting that tiny mark in the middle of the target without taking those first missed shots. Thus, over break, I swallowed my pride and wrote away. Some sections of the project seemed likes bullseyes from the get-go. Others, not so much. Nonetheless, I am far closer to a finished product with this current draft, rough patches and all. From this experience, I learned that writing requires the humility to dive in and work away, knowing that failure, setbacks, and struggle are ahead, but that these are all part of the uneven road toward what will eventually become a product worthy of pride.

Resources for APA (American Psychological Association) Format:

Video Tutorials on creating APA Citations

Video Tutorial on Page Set-up in MS Word

Student & Professional Sample Papers:

Downloadable Template:

- APA Downloadable Template for MS Word without Text

- APA Downloadable Template for MS Word with Sample Text

Resources for MLA (Modern Language Association) Format:

Video Tutorials on MLA Citations

Interactive Practice Building MLA Citations

Student & Professional Sample Papers:

Downloadable Template:

Resources for Chicago Manual of Style:

AMA Style (American Medical Association):

University of Washington Resource

Did you know that there’s a free online “To-Be” verb analyzer?

If you copy and paste small chunks of your final paper into this online tool, it will identify any sentences written in Passive Voice so you can find those instances quickly and correct them by adjusting the subject of your sentence. It’s a great tool to find passive sentences. However, you still need to fix each individual sentence. Check it out here!

By Steph Vasquez

Once, when I was doing my history homework, I was listening to music in Spanish. At the same time, my mother came over to me to ask me something in Spanish, and I responded her in Spanish, while still doing my notes. When I looked down, I realized that my notes, which had started in English, ended up being written in Spanish. When I tried getting back to doing my notes, my brain froze when I tried getting back into writing in English. Multilingual writing can be a bit difficult, especially when it comes to American English academic writing standards.

If you are like me, you probably can’t do work in silence. I like listening to music when I am doing my work. It keeps me on track, and I feel that it helps me work quicker. However, as I speak multiple languages, I also like to listen to music in multiple languages. This is where things can get tricky. In order to keep myself on track when writing, I have a rule when it comes to music: either the music is in the same language, or the music does not have any lyrics. Instrumental music has been a big help in making sure that I am focused on what I am writing.

Another thing I do is that I speak out loud as I am writing. I look very weird when doing it, but this helps me to stay focused and also make sure that I am following proper writing conventions. Usually, you write the way you speak (but beware of informal language and slang!), so speaking out loud as you are writing will help you to pick up on any awkward phrasing. Microsoft Word has a read loud feature in which it will read out any desired section to you.

My very last tip as a multilingual writer is to go to someone else! If you have been writing a paper for a while, your eyes are going to be very tired, and so will your brain. Have someone, preferably someone who has never seen your paper, read it over and give you feedback on it. A fresh pair of eyes sometimes works wonders. And remember, the Writing Center is always here to be that fresh pair of eyes!

The best way to engage your reader is by crafting sentences with compelling action verbs. However, it’s much easier to use dull, passive forms of “to-be” when talking talking about ideas or abstract concepts. When you finish your first draft, it helps to highlight all of the instances of “is”, “are”, “were”, and “was”, and maybe even “have”, “has” and “had” to see how frequently you depend on these verbs. Then you can explore possible alternatives.

Here’s a a worksheet of strong action verbs organized by genre.

There’s certain conventions that you need to know when analyzing a short story or comparing literary works by the same author. For example, you need to know how to write the title: is it in quotes? Is it italicized? Are you using a long quote or a short quote when inserting the text? Do you know how to cite it? Are you writing an analysis opposed to a plot summary? Do you know what tense to use when describing actions that occurred in the work? There’s a lot of rules!

Here’s the Golden Rules When Writing About Literature:

- Don’t summarize, but analyze. Your instructor has read the text and doesn’t need a detailed recap. They are more interested in how you can interpret the text. What do you think is significant about the text?

- Read the text closely. Annotate as you read in order to identify a unique a theme or a idea. We have a digital worksheet to walk you through that process here.

- Have a strong thesis. Check out our resources for thesis statements here.

- Know the literary terminology and use it effectively. Here’s a quick list of terms, definitions, and samples.

- Use the present tense when describing actions in the piece.

- Use the present tense when describing what the author does.

- Remember that the narrator is different from the author.

- Write the author’s name correctly. When you reference the author, write their first and last name the very first time you reference them. Use only the last name when referring to the author later in your paper.

- Use direct quotes from the text. Generally, it’s better to use the quotes than to paraphrase so your reader can see the exact text.

- You must provide an explanation of each quote you provide. What is the significance of the quote? How does it support your thesis? Why did you include it? What does it do/say/indicate?

- Make sure you cite your quotes correctly by using in-text citations. Check out this quick guide. If you have multiple works by the same author, you’ll need to include some extra information.

- Indicate titles correctly. Titles of larger works or containers (like books, plays, anthologies) are italicized. Shorter works within containers (like chapters, poems, short stories) have “quotes” around them.

- Use strong verbs. Let’s avoid “is”, “are”, “has”, “does”, and maybe even move away from “says” and “states”. Check out the list of strong verbs for literary essays here.

- Use good sources. If you have to use other sources, use the databases in the library, not google. Check out these databases first.

- Use your professor’s office hours. Once you have a rough draft, go to your professor’s office hours and see if you’re on the right track. Don’t skip this step. Professors may look for different qualities in papers, and you need to know what they expect from you. For example, I once had an English professor that wanted my paper to contain most of the lecture notes. I later had a English professor that did not what me to use any of the ideas discussed in class. Instead, he wanted my own original ideas about the text. Those are very different expectations!

- Beware of the internet. I know students will browse the internet as a way to get their own ideas flowing. No Fear Shakespeare, GoodReads, and SparkNotes offer chapter-by-chapter interpretations of classical works. That doesn’t mean they are high quality, but they usually have a brief, easy-to-read format, which draws students to them in their brainstorming process. Don’t do it! But, if you can’t resist this temptation, then keep track of each source you read and remember to cite it correctly if you use that idea or a very similar idea anywhere in your paper.

Here’s a detailed handout with examples of how to use these rules.

It’s one of my personal favorites. It provides excellent examples of summary and analysis paragraphs. It also gives you examples of strong thesis statements for literary papers, and it demonstrates a variety of in-text citations with MLA format. I strongly recommend you check it out before you write your next English paper.

Other Tools and Resources:

| Student Sample Essays | Student Sample Essay Paragraph-by-Paragraph |

| Student Sample Essays on Poetry Analysis | Student Sample Paper |

| Upper Level Student Sample Essays | A Compilation of Student Sample Papers from the 200-400 Level Literature Courses |

| Graphic Organizer for Literary Analysis | Multiple Graphic Organizers |

We all have our favorite phrases and “go-to” words. I often find myself repeating these words multiple times in a single paragraph:

Thought Reversals: “however,” “although,”

Thought Extensions: “also”, “and it states”

Interpreting Statements: “so”, “this means that”

On my first draft, the repetition doesn’t matter, but when I start revising, I have to rethink each of those sentences so that I’m not redundant—I want to show that I can articulate my thoughts in a variety of ways to keep my reader engaged.

I’ve found that most college freshmen struggle with building their vocabulary and minimizing the usage of their “go-to” words and phrases. Your vocabulary will grow naturally as you read and become familiar with expressions in your discipline.

However, if the paper is due tomorrow, you may not have that sort of time. You need some tools to expedite that process.

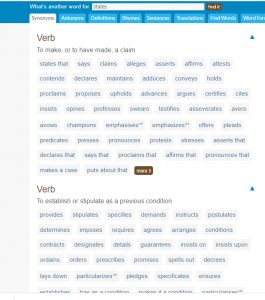

One my favorite tools to eliminate redundancy is https://www.wordhippo.com/.

Here’s why . . .

- You can pull up synonyms, antonyms, definitions, examples of usage, and the most common forms of usage by searching for a single keyword.

- The synonym search works well: it’s broken down by the possible definitions of the original word, and it generates several synonyms on each search.

- You can search for both words and phrases, though it works better with just words.

- Everything is hyperlinked! If you find a new word that’s a synonym, you can click on it to check the definition so that you’re using the new word correctly in your context.

- If you want to use a word that’s unfamiliar to you, you can click to have the word pronounced correctly for you.

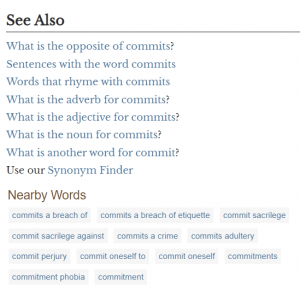

- There’s a “See Also” section that further explains how to use the word in grammatically correct formations.

- Are you taking a poetry writing class? Or maybe you want to embellish a paper with some poetics? This site will generate rhymes for your words and phrases, too.

However, this website is ultimately just a machine pulling up prewritten data—keep that in mind. That means it doesn’t give you the connotations for the specific keyword (so if you are replacing a negatively charged word like “stuffy,” you may accidently insert a positively charged word like “cozy”. ) It also doesn’t say if the synonym has any slight differences from the original word on the landing page, and that could lead to using words that don’t express exactly what you mean. Last, it doesn’t work well with field-specific vocabulary.

Still, I’d recommend this resource for eliminating word-choice redundancy, and you’ll find that as you search for more and more words, you’ll acquire more and more words.